American politics have taken on a déjà-vu feeling for Venezuelan-Americans, many of whom say the 2020 race recalls the decades-long political fractures experienced back home by millions of Venezuelans.

Ever since former president Hugo Chavez took power in 1998, Venezuelans have been divided between those who supported him, dubbed chavistas, and those who opposed him, the anti-chavistas. Families were torn apart by political violence. Fathers would stop speaking to their children because they voted for Chavez, or against him.

Now as the US election approaches, similar bitter divisions exist between Americans who are in favor of President Donald Trump and against him, say some Venezuelan-Americans. “It’s surreal,” Mery Montenegro, 37, who left Caracas in 2015 and now works in advertising in Washington, DC, told CNN. “It’s like reliving everything you marched for, everything you lived through back home.”

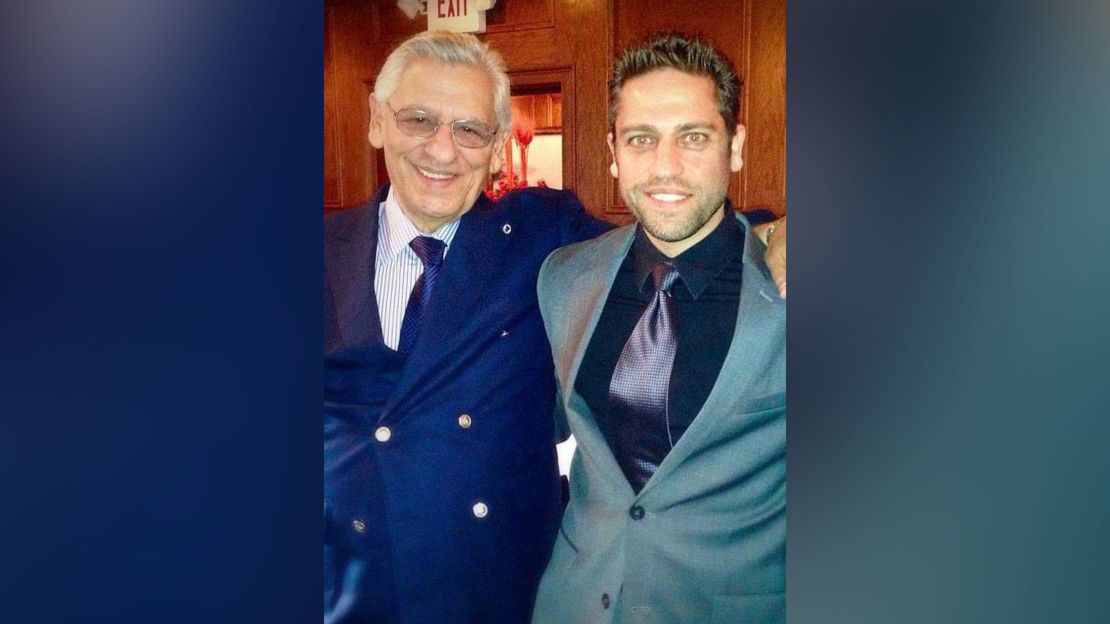

Joaquin Perez and his son Alberto, both naturalized US citizens now, are split over the 2020 election: Joaquin will vote for Biden, while Alberto will vote for Trump. In Venezuela, they both opposed Chavez. But while they agree that Trump has many traits in common with the late populist socialist Venezuelan leader, they’ve come to opposite conclusions about what that means.

Though they stand on opposite sides of the political spectrum, Trump, like Chavez, is a charismatic leader who claims to defend the interest of the people against corrupt elites. Both men entered politics from the outside, Trump as a businessman and Chavez as a soldier, both promising change and reform to a stale political scene.

“Trump is the same as Chavez, the same as Fidel [Castro],” Joaquin said. “You spend your day constantly listening and asking yourself ‘What is he going to say today?’”

Alberto agrees that there are similarities, but says that’s not what matters. “Trump’s likeness with Chavez is self-evident, it gives me shivers; but you must understand that what destroyed Venezuela was not Chavez’s charisma but his criminal and socialist policies,” he told CNN.

‘What is he going to say today?’

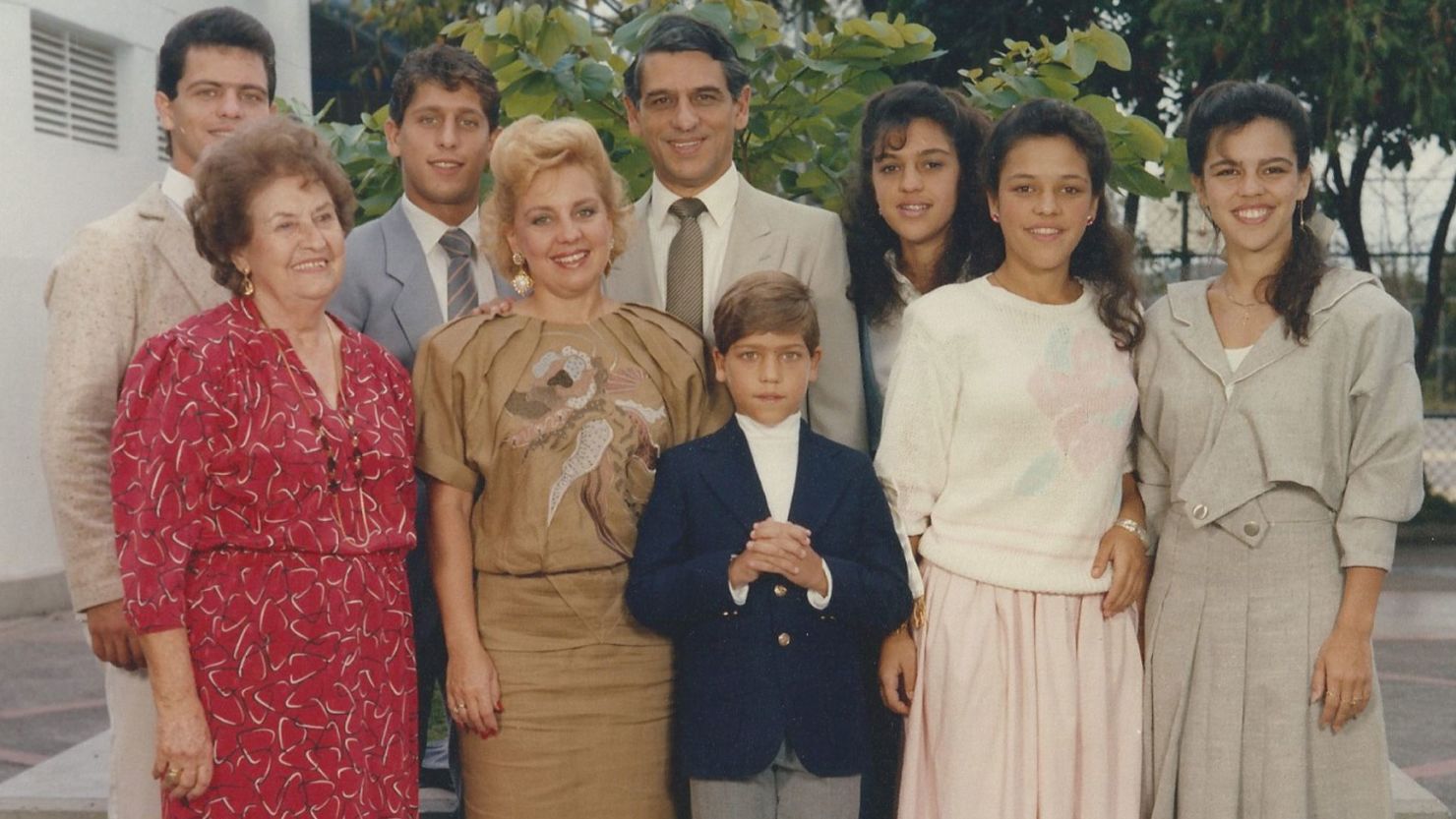

Joaquin Perez was born in Cuba and left for Venezuela in the 1960s after the communist takeover. He married and had seven children in Venezuela. All but one now live abroad.

After a political career and serving in cabinet in Venezuela in the 1970s and 80s, Perez migrated again to Miami when Chavez took power. Now eighty years old, he says he feels he is now living under a leader with authoritarian tendencies for the third time.

Like Perez, the majority of Venezuelan-American voters live in Florida, a crucial swing state and one of the reasons why both candidates are paying close attention to the community.

Perez feels very involved in the 2020 campaign not only for the choice he faces as an American citizen, but also because the consequences this election holds for US policy towards Venezuela.

In the last seven years, Venezuela has suffered one the harshest economic collapses outside a war zone in recent history. While the government of embattled Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro blames US sanctions for the crisis, years of domestic mismanagement and chronic corruption have also squandered the country’s immense oil wealth.

Today, 96% of Venezuelans live in poverty, according to an independent investigation by three leading universities in Caracas. Protests against Maduro, Chavez’s hand-picked successor, have often been met with force—the United Nations has documented alleged extrajudicial killings and other violations of human rights by government forces.

The Trump administration has taken a tough stance against Maduro, slamming sanctions on top government officials including Maduro himself and operating a de-facto embargo against the Venezuelan oil sector with the aim to topple him. In January 2019, the White House recognized opposition leader Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s interim president, a move followed by more than 50 countries around the globe.

However, this pressure campaign has so far failed bring any change in Caracas.

Perez thinks Trump never really prioritized freedom in Venezuela. “Trump created the expectation that he could topple Maduro, but he knew he could not do it. It was a political move that eventually turned out well for him, because many people supported it here in Miami, not so much for Venezuela.”

Joaquin hopes a Biden presidency would follow Barack Obama’s footsteps and engage in talks with Cuba and Venezuela to promote democracy, in opposition to Trump’s confrontational approach.

So far, Biden’s most concrete overture to the Venezuelan community has been his promise to create a Temporary Protective Status (TPS) framework for Venezuelan migrants, which would shield them from deportation.

‘I bet on ‘America First’ by choosing to come here’

In February, Guaido, president of the opposition-controlled National Assembly, was invited as a guest of honor to Trump’s 2020 State of the Union address in Washington, DC. “Please take this message back that all Americans are united with Venezuelans in their righteous struggle for freedom,” Trump told the opposition leader from his podium, in what now appears to have been the apex of Trump’s overture to Venezuela and Venezuelan-Americans.

Unlike his father, Joaquin’s son Alberto, 41, believes Trump’s approach to pressuring the Venezuelan government and his embrace of Guaido was genuine, and views the Trump administration’s economic pressure on the country as necessary. He blames Guaido for not taking full advantage of White House support – the opposition missed its opportunity to seize power by failing to formally request a military intervention by the United States, Alberto says.

And while the next President’s approach towards Caracas is high in the priority list of Miami voters like Joaquin, it’s less important for Alberto, who teaches music in a rural community in the Appalachian Mountains in Georgia and is drawn to Trump’s economic message.

“Trump is an American brand. His arrogance, his confidence are all American. He’s as American as the apple pie. When he says ‘America First’ it’s something that makes me feel included. I bet on ‘America First’ by choosing to come here after leaving Venezuela,” Alberto says.

Although he does not think a Biden presidency would make the US “a Venezuela on steroids” as Trump has threatened, Alberto is suspicious of what he sees as Biden’s overtures to America’s left. While the Democratic candidate says he is no socialist, Alberto says, “Fidel [Castro] never said he was a socialist, until he was one. Chavez said many times he was not a socalist, until he was one.”

Joaquin’s other children who live in the US have not taken a firm position on the election, and politics rarely pop up in family conversation. In the end, both the father and son believe their mutual affection is stronger than their conflicting views.

But online, the debate within the Venezuelan-American community is fierce. Montenegro said she had to leave a Facebook group for Venezuelans in Washington because the arguments among members were never-ending.

And while Venezuelan-Americans are looking at the US elections as a consequential event for the future of Venezuela, their votes in Southern Florida are highly coveted by both candidates.

Notably, when Joe Biden spoke in Miami on October 5, the person tasked with introducing the presidential hopeful was not a Cuban American, by far the most politically vocal ethnic group in South Florida. Instead it was the daughter of Venezuelan immigrants, who will cast her first vote next month.

Journalist Nicole Kolster contributed to this report